By Martin Van Staden

What needs to happen before South Africans realize that the institution of government is not a friend, a servant, or a protector, but a rival that only does good insofar as it is restrained? Our continued trust in government enables its continued expansion and its tendency toward corruption.

The Problem

My recent article on the Western Cape provincial government’s decision to implement an authoritarian alcohol policy sparked quite a bit of controversy which I expected, and preempted in the article itself. Despite South Africans’ daily lived experience telling – shouting at – them that government only undermines them, the institution still enjoys widespread trust, not only in the Western Cape under the Democratic Alliance (DA), but nationally.

This is a particularly grave problem in South Africa due to what I consider to be a fundamental error in our constitution. But, moreover, it is a problem because those who trust government are invariably unaware of the nature of government.

On 24 April 2016, the former liberal and former DA leader Tony Leon wrote a valuable opinion piece in the Sunday Times, titled “Nkandla excesses exposes the glaring gap in founding law”. This article came only weeks after President Jacob Zuma confidently toldAfrican National Congress (ANC) supporters that the Rule of Law can be changed with a majority in Parliament. Those who who are a little more legally aware would know that the Rule of Law is not a rule of the law, but a doctrine which, as Judge Tholakele Madala and legal scholar Professor Friedrich von Hayek both said, permeates all law.

(The subeditor who chose Leon’s article title was incorrect in describing the Constitution as our “founding law”, as there has been complete legal continuity in South African constitutional law since 1910. The founding law of South Africa as we know it is the South Africa Act of 1909, passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Constitution is, instead, our supreme law.)

The article summarizes South Africa’s problem: We enacted a constitution for a moral saint – thought to be Nelson Mandela – and not for a real human being. As libertarians in South Africa and abroad had been warning for decades (centuries, if one counts early classical liberal thinkers), the nature of government means that those who are inevitably attracted to government are people who seek power. This is an absolute rule. There is no reality in which the institution of government does not attract this type of human being. This problem cannot be eliminated. It can, however, be tempered and suppressed, and for that to happen, certain institutions need to be entrenched in political society.

Indeed, if is often said – but rarely heeded – that when a constitution is being drawn up, the drafters must imagine that their very worst political enemy will be in government under the framework they devise. As Leon Louw has said in the past, at constitutional negotiations (like the one that brought Apartheid to an end) the party which will govern after the Constitution is adopted should be chosen at random (say, by a draw). On that basis, the drafting of the Constitution should commence. Thus, between the National Party and the ANC, each of the parties should have participated in the constitutional drafting on the assumption that it is the other which will govern. In this way, the best constitution would have been made: One which limits and decentralizes government.

It must be emphasized that when contemplating a political solution to a problem or devising a new political framework, the answer will always lie with institutions, and never with individuals – not “uniter” Nelson Mandela, not “outsider” Donald Trump, not “capitalist crusader” Herman Mashaba. These institutions must be both customary and legal, meaning that not only should there be strong legal restraints on government, but it must become unthinkable for those in government to do certain things.

The Nature of a Constitution

One of these (legal) institutions is a constitution.

A constitution, properly understood, is a special type of law that, unlike other laws, addresses itself to the government (not the people) of a society, and lays out what that government may, and crucially, what it may not do. The core message of constitutionalism is everything which is not allowed is forbidden. Constitutions are one of those things a society cannot afford to get wrong, because they are not transient, and it should always be assumed that governments will try to interpret them in a manner that benefits them.

The Constitution of South Africa, unfortunately, reads like a constitution meant to be transient. The Preamble and the Bill of Rights are filled with references to Apartheid, which will render it an awkward read for someone in the year 2117. This fundamental error undermines the constitutional (rigid, fixed) nature of a constitution by, essentially, giving South Africa a weird temporal status: We will always be stuck just after Apartheid. Time stands still legally.

In the Preamble we “recognise the injustices of our past” and set out to “heal the divisions of the past”. In the property rights provision, government is empowered to secure tenure which has been rendered “insecure as a result of past racially discriminatory laws”, and people who were dispossessed “after 19 June 1913 as a result of past racially discriminatory laws” may seek restitution or other redress for such dispossession. (As an ardent proponent of restitution, I believe this could have been framed far more appropriately, without using words like “past” or specific dates. Besides, the rei vindicatio action exists in our law anyway, allowing true owners to get possession of their property back.) Similarly, government is empowered to take measures to realize the right to education “taking into account the need to redress the results of past racially discriminatory laws”.

Examples like this abound.

The United States’ Declaration of Independence was a transient document, filled with references to the oppression of the British Empire. It was not a constitution, but a legal instrument which served one purpose and did so within a short space of time. Decisive executive action was naturally required for the Twelve Colonies to separate from the Empire. The war was fought and won. The U.S. Constitution was not meant as “a contract or a statute”, writes Professor Stephen Macedo in The New Right v. The Constitution, “but a majestic charter for government, intended to govern for ages to come and to apply to both unforeseen and unforeseeable circumstances.”

South Africa’s constitution, also presumably meant for the ages, has bound us up (theoretically) in perpetuity with the legacy of Apartheid and the requisite decisive executive action that goes with solving it. Our war against the legacy of Apartheid was made legally permanent and with it, an excessively powerful executive government was made similarly legally permanent. As a consequence, South Africa’s courts have time and time again reaffirmed the principle that because of the legacy of Apartheid, government must have extraordinary powers to deal with it. While the judges themselves might not realize it, this has directly enabled the kind of corruption we see today.

The Rule of Law

Another important legal institution that needs to be entrenched in any society that seeks to be free, is the Rule of Law.

To simplify, the Rule of Law means that society is governed by proper law, and not by the whims of man. The whims of man often take the form of law, but lack the legitimate character of law. (Indeed, do not confuse rule by law with the Rule of Law.) Proper law are rules informed by reason, evidence, and the time-tested principles of law, like rigidity, predictability, certainty, and proportionality. Libertarians would add to this and say that proper law are those rules which have a basis in the social contract: That government exists only to protect people and their property, and that in return people have sacrificed their natural ability to be violent in pursuit of their goals.

The Rule of Law is formally entrenched in South African law per section 1(c) of the Constitution, which states that South Africa is founded on the supremacy of the Constitution and the Rule of Law. But while the supremacy of the Constitution has seen relatively broad recognition, the co-equal supremacy of the Rule of Law has been afforded lip-service. From Herman Mashaba dropping “the rule of law must be upheld!” in every new Facebook post to Jacob Zuma ostensibly calling for the Rule of Law to be respected (but thinking it can somehow be ‘changed’ in Parliament), everyone knows about the Rule of Law, but very few people think of it as something consequential.

Research done by the Free Market Foundation appears to indicate that virtually all legislation passed by Parliament violates at least one tenet of the Rule of Law. For instance, essentially all laws which empower executive officials to make decisions, like create regulations or ‘determinations’, does so without any guiding criteria (save perhaps for the cop-out “public interest” criterion), meaning that it is the whim of man rather than the Rule of Law which governs in that particular respect. From mining licenses, to private school licenses, to healthcare regulations, officials have all the discretion in the world, and, in effect, create law which we must abide by. This latter function is supposed to be the domain of Parliament, not officials.

This, obviously, enables corruption.

If a regulator has the power to revoke or not renew a license without having to adhere to any strict criteria, it follows that companies will not want to sour their relationship with the regulator. It follows that bribes become a very likely occurrence. Arbitrariness and corruption are two sides of the same coin.

The courts, too, have tended to ignore the Rule of Law under the guise of ‘deference’. They endorse a minimalist notion of the Rule of Law whereby Parliament or the executive must simply act in accordance with the provisions of existing legislation, regardless of whether the legislation itself violates the Rule of Law. Where the courts have admitted that legislation violates the Rule of Law, like the Currency and Exchanges Act, they have refused to declare them unconstitutional, because, for some reason or another, the courts are unwilling to put two and two together, and understand that the Constitution provides for the co-equal supremacy of both the Constitution and the Rule of Law. It must, thus, follow that anything inconsistent with the Rule of Law is unlawful.

In South Africa, the apparent mixture of transience and permanence in our constitution, coupled with the fact that the Rule of Law has not been respected for centuries, has an oppressive and corrupt government as a consequence.

Jacob Zuma has simply reaped the rewards of an errant system of government. He did not create it. He sought power, which was handed to him on the silver platter known as South African constitutional jurisprudence.

Be Conscious of the Nature of Government

This situation is, however, not hopeless.

We must be careful not to think that ridding ourselves of Zuma is the key to return to liberal constitutional democracy; it is not.

Instead, the first step to moving in the direction of accountable and constrained governance is consciousness.

All it takes to turn the tide, is for South Africans to realize the true nature of government. Everything else will fall into place as a natural consequence of that realization, and nobody will be worse for wear. It is not a zero-sum game. This realization comes at the expense of nothing and nobody, save perhaps for corrupt politicians and their cronies.

Force, compulsion, coercion, and violence are the essence of government. These characteristics are inseparable from that institution, and rightly so – government, as a concept, came about because of the need for a forceful institution to protect individual rights. But just like one does not appoint a mercenary to run a nursery for babies, one should not appoint government to do anything other than protect persons and property from violence or fraud. This is what government is supposed to be limited to, and why force is a crucial ingredient to its nature. But government has not been kept to its proper role, and we have been reaping the fruit of this grave mistake for centuries. This is why acknowledging and appreciating the nature of the institution of government is key to solving all the problems which have resulted from this mistake.

When, or if, South Africans start this process of acknowledgment and appreciation, things like the Western Cape alcohol policy will become impossible. The Western Cape government would not be able to pass such a policy if it did not have broad appeal, which it clearly and ignorantly does have. Similarly, the entire notion of tenderpreneurship would immediately fall away. The over-reliance on government education and healthcare will end at once as communities, now disgusted by the very idea of government involvement in those things as a means of social control, band together and establish community-run private schools and clinics.

Legal and political scholars have been trying to evade the nature of government for centuries. They often acknowledge the general principle that government is a violent institution which must be constrained to only its social contract duty to protect person and property, “but”, they say, this or that circumstance necessitates a greater role for government.

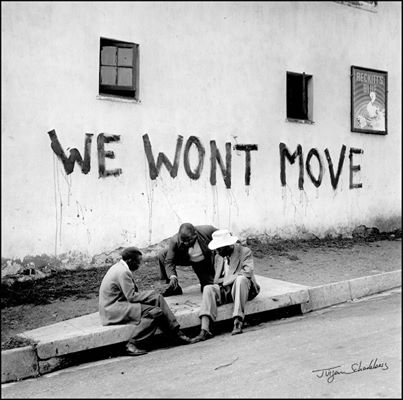

In South Africa today, the “but” is the legacy of Apartheid. During Apartheid, the “but” was the possibility of black domination over the white minority. During the prior century, the “but” was the proximity between the British and the Boers. During the early Cape settlement, the “but” was the isolated location of the colony. There is always a “but” which has the effect of defeating the general principle.

It is, and has always been, high time to stop with the “but”. The “but” has only ever created more problems and more cause for more even more “buts”. This will continue unless people draw a line in the sand. This might sometimes mean forgoing the possibility of revenge or advancing certain group interests, but it is absolutely necessary to kick-start a free and prosperous society.

Conclusion

For as long as South Africans continue to envision the solution to our problems to be found in government, will we continue down this endless cycle.

This applies not only to the Democratic Alliance as well, but especially to the Democratic Alliance, because the DA now finds itself in many people’s political blindspots. One never truly appreciates the nature of government if particular organizations or individuals are caught in their blindspots. Nobody is exempt from the nature of government as a forceful institution which can inherently overpower any non-governmental actor for any reason. Whether it is me, Herman Mashaba, Pravin Gordhan, Donald Trump, Barack Obama, or Jacob Zuma in charge of government, the nature of government never changes.

Trust in yourselves, first and foremost, and in your families and communities. Never trust government, especially if it says it seeks to help, and especially if it is ‘your guy’ who is in power.

Recent Comments